National Antimicrobial Resistance Monitoring System (NARMS)

The National Antimicrobial Resistance Monitoring System (NARMS) is an interagency, collaborative partnership with state and local public health departments, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA).

This national public health surveillance system tracks changes in antimicrobial susceptibility of select foodborne enteric bacteria found in ill people (CDC), retail meats (FDA), and food animals (USDA). The NARMS program at USDA focuses on two sampling points—samples collected from intestinal (cecal) content and carcass or food commodity samples.

NARMS Agency Partners

1996

1997

2002

NARMS Partners – FSIS, FDA and CDC – publish Salmonella and Campylobacter Macrolide Antimicrobial Resistance/Cross-resistance Findings

Read this studyNARMS Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR) data are now available in the Annual Report format

View the AMR Annual ReportsNARMS Minor Species Antimicrobial Resistance Findings (2020-2022)

Read the Study- Monitor trends in antimicrobial resistance among enteric bacteria from humans, retail meats, and animals.

- Disseminate timely information on antimicrobial resistance to promote interventions which reduce resistance among foodborne bacteria.

- Conduct research to achieve better understanding of emergence, persistence, and spread of antimicrobial resistance.

- Provide data that assists FDA in decision making involving the approval of safe and effective antimicrobial drugs for animals.

2024

- NARMS Integrated Report CY 2021 and Antimicrobial Resistance Trends in Salmonella

- NARMS at USDA FSIS: A Robust Source of AMR Data and Information

- Increase in the Frequency of Salmonella Enteritidis with Decreased Susceptibility to Ciprofloxacin

2023

- FSIS NARMS: One Health Approach and FY 2024 Lamb and Sheep Study

- NARMS Findings from the 2020 Integrated Report

- FSIS and the National Antimicrobial Resistance Monitoring System (NARMS): The Public Health Impact of NARMS

2022

2021

2020

In 2002, NARMS began collecting retail meat samples. This component is led by FDA’s Center for Veterinary Medicine (CVM). Retail meat surveillance is conducted through partnerships with different states, universities, and public health departments. Participating sites purchase chicken, ground turkey, ground beef, and pork chops at retail outlets and culture them for nontyphoidal Salmonella and Campylobacter. Additionally, 11 sites also culture retail meats for E. coli and 9 sites culture for Enterococcus. Additional information is available at FDA NARMS.

In 1996, NARMS began collecting antimicrobial resistance data from ill people on select enteric bacteria transmitted commonly through food. This component started within the framework of CDC’s Emerging Infections Program and the Foodborne Diseases Active Surveillance Network (FoodNet). Human surveillance began in fourteen sites in 1996 and became nationwide in 2003. CDC performs AST on approximately 5000 human isolates per year. Additional information on CDC NARMS is available at https://www.cdc.gov/narms.

FDA, CDC, and USDA collect data from farm to fork to accomplish the NARMS objectives. NARMS data and reports are available on FSIS and partner agency websites. In addition, each year, NARMS publishes an Annual Integrated Report that summarizes the most important resistance findings from the three participating Agencies for Salmonella and Campylobacter, as well as for E. coli and Enterococcus. This report includes summary data tables, isolate level information and interactive data displays to enhance data visualization.

FSIS

- Quarterly Sampling Reports on Antimicrobial Resistance

- Laboratory Sampling Data

- Strategy to Address Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR)

FDA

- NARMS Interim Data Updates

- NARMS Minor Species Report | FDA

- NARMS-FDA

- NARMS Interactive Tableau Displays

CDC

The antimicrobial drugs selected for testing are based on their importance in human and veterinary medicine and for their utility as epidemiological markers for the movement of resistant bacteria and genes between environments. NARMS partners test for bacterial susceptibility to a range of antimicrobial drugs which include 15 antimicrobial drugs for Salmonella and E. coli, 9 for Campylobacter and 16 for Enterococcus. Selected antimicrobials/antimicrobial drug classes are also ranked, by FDA, as Critically Important, Highly Important and Important using similar criteria. The specific factors and the criteria to rank the importance of antimicrobial drugs are outlined in FDA’s Guidance - GFI #152.

Whole genome sequencing (WGS) technology has become a routine part of NARMS surveillance to screen for resistance genes in enteric bacteria. Use of WGS can provide better isolate resolution including resistance genes and mobile elements and help link human and non-human resistance data.

- National Action Plan for Combating Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria Progress Report: Fiscal Year 2022

- Long-Read Sequencing Reveals Evolution and Acquisition of Antimicrobial Resistance and Virulence Genes in Salmonella enterica

- Novel linezolid resistance plasmids in Enterococcus from food animals in the USA

- Proposed Epidemiological Cutoff Values for Ceftriaxone, Cefepime, and Colistin in Salmonella

- Comparative Analysis of Extended-Spectrum-β-Lactamase CTX-M-65-Producing Salmonella enterica Serovar Infantis Isolates from Humans, Food Animals, and Retail Chickens in the United States

- Identification of Plasmid-Mediated Quinolone Resistance in Salmonella Isolated from Swine Ceca and Retail Pork Chops in the United States

- National Antimicrobial Resistance Monitoring System: Two Decades of Advancing Public Health Through Integrated Surveillance of Antimicrobial Resistance

- WGS for Genomics and Food Safety

- Chicken parts – performance standards, serotypes and AMR

- Extraintestinal Pathogenic Escherichia coli

- Food and Drug Administration NARMS Website

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- World Health Organization (WHO)Antimicrobial Resistance Website

- President’s Advisory Council on Combating Antimicrobial Resistant Bacteria (PACCARB)

- Antimicrobial Resistance Overview (AMR) (USDA)

- USDA One Health Website

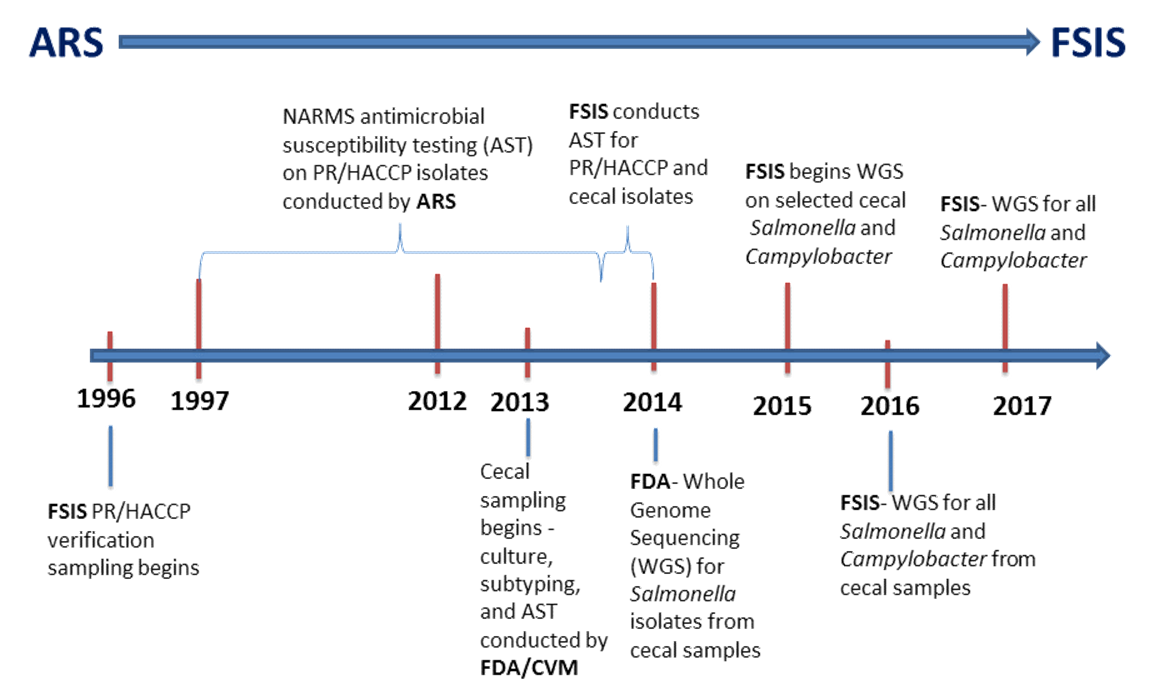

In 1997, NARMS began collecting data on food animals which was led by the USDA Agriculture Research Service (ARS) through 2013. Antimicrobial susceptibility testing (AST) for non-typhoidal Salmonella began in 1997 on isolates collected from raw meat and poultry products at all slaughter facilities across the United States under the Pathogen Reduction Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Point (PR/HACCP) program. Sample types have changed over the years depending on FSIS directives: carcasses of cows/bulls, steers/heifers, market hogs1, broilers (young chickens), ground beef, ground chicken and ground turkey. Testing later expanded to include Campylobacter (1998), E. coli (2000), and Enterococcus (2003) isolated from chicken carcasses.

ARS discontinued AST of Enterococcus in PR/HACCP chicken isolates in 2012 and E. coli in 2013. Those organisms are currently tested from food animal ceca and retail meat samples. In October 2013, FSIS assumed responsibility for the AST of NARMS PR/HACCP isolates.

In March 2013, NARMS began the cecal sampling program - a collaborative effort between the FDA's Center for Veterinary Medicine (CVM) and FSIS. Samples from cecal contents are collected at slaughter facilities of selected food animals and analyzed for Salmonella, Campylobacter, Escherichia coli, and Enterococcus. The food animals that are sampled include young chickens, young turkeys, dairy cattle, beef cattle, market hogs, and sows.

In 2014, the FDA began whole genome sequencing (WGS) on Salmonella isolates collected from the cecal program. Today, FSIS performs WGS on all Salmonella and Campylobacter isolates collected from both the PR/HACCP and cecal programs

1 FSIS suspended scheduling cows/bulls from sampling in 2011 and market hogs and steer/heifers in 2012 because of the low number of positive samples.

Background

The Food Safety and Inspection Service (FSIS) is the public health agency in the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) responsible for ensuring that the nation's supply of meat, poultry, and egg products is safe, wholesome, and correctly labeled and packaged. As part of its mission, the FSIS uses guidance from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to routinely verify that meat, poultry, and egg products intended for human consumption are free of illegal antibiotic residues (i.e., fall below the maximum levels allowed by law).

The FDA approves new animal drugs, including antimicrobials and antibiotics, for use in food-producing animals. To ensure that the use of approved antibiotics does not cause harm to human health through the consumption of animal-derived food products, the FDA establishes animal-specific conditions of use for antibiotics, acceptable antibiotic withdrawal periods, and tolerance levels (i.e., the maximum levels allowed by law) for antibiotic residues in animal tissues or products. The following questions-and-answers are intended to raise awareness of antibiotic-related terms and highlight the safeguards that prevent meat, poultry, and egg products contaminated with illegal antibiotic residues from entering the food supply.

Q: What is an antibiotic?

A: Antibiotics are drugs that kill or prevent the growth of bacteria.

Q: What is the difference between antibiotics and antimicrobials?

A: Antibiotics are drugs that only kill or prevent the growth of bacteria. Antimicrobials are drugs that kill or prevent the growth of a variety of microorganisms, including bacteria, viruses, fungi, and parasites. All antibiotics are antimicrobials, however, not all antimicrobials are antibiotics.

Q: Why are antibiotics used in food animal production?

A: Antibiotics can be critical in the treatment of ill animals and in limiting the potential spread of infections.

Q: Are antibiotic residues the same as antibiotic resistance?

A: No. An antibiotic residue is a small amount of leftover drug, or parts of the drug that are not completely broken down by the animal’s body. These residues can be identified in animal products or tissues. Antibiotic resistance is a process where the bacteria that the antibiotics are intended to kill or inhibit have adapted to them, making the drugs less effective. The presence of antibiotic residues in an animal doesn’t necessarily mean that the animal is infected with antibiotic resistant bacteria, and vice versa.

Q: What is an illegal antibiotic residue?

A: An illegal antibiotic residue is a potentially harmful amount of an antibiotic that remains in an animal’s system at the time of slaughter. For animals intended for human consumption, testing for residues occurs after the animal is humanely slaughtered for processing.

Q: If an antibiotic is used in food animal production, what safeguards are in place to ensure that meat, poultry, and egg products on the market are free of illegal antibiotic residues?

A: For each antibiotic used in livestock or poultry production, an FDA-approved withdrawal period is observed before the food animals go to slaughter and products from these animals enter the food supply. This is known as the “withdrawal time.” Withdrawal times reflect the amount of time necessary for animal tissue to process a drug so that the amount remaining in the tissues has decreased to a safe level. Every FDA-approved drug for food animals has a withdrawal time printed on the product label. Additionally, withdrawal time charts for different species and antibiotics are widely available from producer groups and cooperative agricultural extension websites. To ensure compliance with these guidelines and provide confidence in the food supply, each year, FSIS tests thousands of meat, poultry and egg products under the U.S. National Residue Program (NRP).

Q: What is the U.S. National Residue Program (NRP)?

A: The NRP is an interagency program carried out by the FSIS, the FDA, and the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) that was developed to identify, rank, and test for chemical residues (including antibiotics) in meat, poultry and egg products. The NRP is designed to: (1) provide a structured process for identifying and evaluating chemical compounds of concern in food animals; (2) analyze for chemical compounds of concern; (3) report results; (4) investigate drug residue violations; and (5) if required, implement enforcement action at the farm/producer level. Under the NRP, FSIS verifies that meat and poultry processing plants throughout the United States monitor residues through sampling and testing products. Overall, very few animal products are found to have residue violations. For example, in 2017, FSIS found residue violations in less than 1% of routinely scheduled domestic samples. Meat, poultry, and egg products found to contain illegal antibiotic residues are condemned and do not enter the food supply.

Q: How can consumers help keep their food safe and reduce the chance of illness from bacteria in meat and poultry products?

A: FSIS recommends that consumers cook all meat and poultry to proper internal temperatures to kill bacteria and other foodborne pathogens. Consumers should also practice four simple food safety tips: clean, separate, cook, chill.